The briefest of brief histories of The National Viewers & Listeners’ Association, the Director Of Public Prosecutions and the 1984 Video Recordings Act. Or, if you prefer, “How Things Got Nasty!”

Picture this. It’s 1965. England. It’s probably raining. Running the country is the Labour party’s pompous pipe puffing Harold Wilson. Thunderbirds are flying for the first time on TV, Churchill has just died, Round The Horne is camping it up on the radio, Yesterday is in the charts and Help! is at the movies. Dads are reading Ian Fleming and mums are daring to try Mary Quant’s new miniskirts. It’s the mid-sixties. Think The Knack and How To Get It, for the visuals, rather than Austin Powers.

While all this goes on, over a milky cup of tea in middle England, a 55 year old woman is about to change the face of British Horror movies. Yep. Pretty much without even upsetting her cuppa.

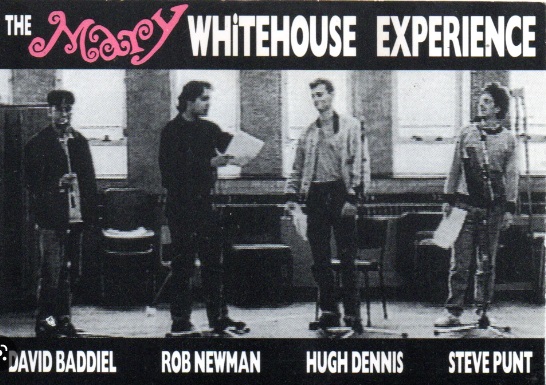

Mary Whitehouse. A name to strike a variety of feelings in a number of folk, depending on who they are. For some, a well-meaning decent woman wanting the best for her country and countrymen. For others, a prim, uptight, shrieking fusspot busybody who longs for the Victorian age when there were skirts on the piano legs and side-whiskers on every gentleman. For those born around 1976, it’ll be the name of a British comedy sketch show and a weird one at that.

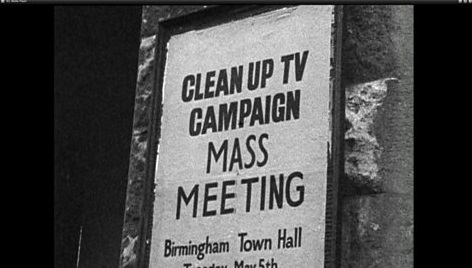

But we’ll get to her infamy later. In 1965 Mary is at her kitchen table, pen in one hand and rich-tea biscuit in the other, championing her cause to clean up the television of the United Kingdom. Too much rudeness, too much filth, too much sex, too much swearing, too much idleness… Too much of anything that isn’t wholesome Enid Blyton-y Christian fayre. She and her husband Ernest, along with a local Reverend, have been running a slowly growing Clean-Up TV Campaign for a year or so.

Nipping at the heels of the then director of the BBC, Hugh Greene, Whitehouse and her half-million petition signatories fell into action as they saw the era’s broadcasting, in their words, as “the propaganda of disbelief, doubt and dirt … promiscuity, infidelity and drinking.” In place of this, they argued, the BBC’s activities should “encourage and sustain faith in God and bring Him back to the hearts of our family and national life.”

You get the idea. We catch up with Whitehouse and Co as they get more official and officious than just harmless petitions and letter-writing about “standards” when in 1965 she and her gang founded the National Viewers & Listeners Association. The Premier League of complainers, as opposed to the softer 3rd division she’d been kicking around with ‘til then. She brought in Christian activist Charles Oxley to act as Vice President and the organisation started to go toe-to-sling-back with film-makers, producers, play-writes and broadcasters to remove the “bad influence” she felt radio and television was having on the country’s moral fibre.

This woman and her activists were more than just neighbourhood busybodies. It is alleged that her group’s persistent and prickly letters that bombarded Harold Wilson and his government in the sixties caused all sorts of political hot potatoes. (Certainly hotter than any of the sex she would permit on television). Belligerently demanding action, responses, apologies and redactions, civil servants reportedly just began to “lose” Whitehouse’s letters to avoid the stresses and strains of having to answer to this flag-waving troupe of Christian evangelists.

Popping up on right-to-reply TV shows, news items, magazine shows and daytime TV, Whitehouse’s bespectacled face became a regular feature on the BBC as she moaned and mooed and spoil-sported everything over the next few years she and her Association felt wasn’t “for the good of the country”: War coverage met with her objections. Editor of Panorama Jeremy Isaacs received a letter from Whitehouse complaining about his decision to repeat Richard Dimbleby‘s coverage of the liberation of the Belsen concentration camp.

She complained about this “filth” being allowed on air as “it was bound to shock and offend.” Peter Watkins‘ mock-documentary The War Game led to Whitehouse writing that nuclear war was, “too serious a matter to be treated as entertainment.” Vietnam coverage was another bugbear, the NVLA stating: “…the horrific effects on men and terrain of modern warfare as seen on the television screen could well sap the will of a nation to safeguard its own freedom, let alone resist the forces of evil abroad.“

But it was more than just bloodshed and politics. Famously, once Whitehouse’s dander was up, almost everything could be found to be worthy of her missiles and missives. The BBC sitcom ‘Til Death Us Do Part lead to her comment: “I doubt if many people would use 121 bloodies in half-an-hour,” and “Bad language coarsens the whole quality of our life. It normalises harsh, often indecent language, which despoils our communication.”

Benny Hill’s dancers were inappropriate, comedian Dave Allen was “offensive, indecent and embarrassing.” Play write Dennis Potter’s work on the BBC was “…a conspiracy to remove the myth of god from the minds of men.“

Children’s TV was no safer. 25 years later, Reverend Lovejoy’s wife Helen in The Simpsons would have had a great deal in common with Whitehouse in their mutual “think of the children!” hysterics. The family sci-fi adventure Dr Who for some reason seemed a stone in the flat-shoe of the aging Whitehouse. She described the serial Genesis of the Daleks (1975) as consisting of “teatime brutality for tots,” said The Brain of Morbius (1976) “contained some of the sickest and most horrific material seen on children’s television“, and on The Seeds of Doom (1976), in which the Doctor (Tom Baker) survives an encounter with a giant carnivorous plant monster, commented: “Strangulation—by hand, by claw, by obscene vegetable matter—is the latest gimmick, sufficiently close up so they get the point. And just for a little variety, show the children how to make a Molotov cocktail.”

I take personal delight in the fact that the Number One pop single in the UK on my birthday caused Mrs Whitehouse some distress. As I screamed, whimpered, wee-ed and wriggled blinking into the daylight on Nov 28th 1972 in North London, Chuck Berry’s novelty rock n roll clunker “My Ding-A-Ling” had Whitehouse reaching for the Basildon Bond and a fresh pot of Quink. We have to assume it was the continued wanking euphemisms (“both hands holding my dingalingaling…” etc) rather than the uninspired guitar work or shoddy live recording.

Although fair’s fair, her campaign to stop Alice Cooper‘s “School’s Out” being featured on Top of the Pops was successful. However Cooper sent her a bunch of flowers, since he believed it was her publicity that helped the song to reach number one.

We’ll get to this inevitable reverse-effect later. As you would imagine, shoving something on the front page for its “awfulness” is at least one way to get listeners desperate to find out more about it and have it climbing the ratings.

Which brings us to movies. In 1971, Whitehouse and Co. grabbed Stanley Kubrick by his Oranges. His film version of Anthony Burgess’s novel had many folk complaining of the dangers of “copycat” violence. Famously Kubrick himself responded to the controversy by requesting the film’s withdrawal from distribution in 1973, although with the accompanying statement:

“To try and fasten any responsibility on art as the cause of life seems to me to put the case the wrong way around. Art consists of reshaping life, but it does not create life, nor cause life. Furthermore, to attribute powerful suggestive qualities to a film is at odds with the scientifically accepted view that, even after deep hypnosis in a posthypnotic state, people cannot be made to do things which are at odds with their natures.”

Well said Stanley. Although let’s face it, if the public couldn’t be bullied, encouraged, egged and pestered into behaviour it might regret, we wouldn’t have advertising.

Whitehouse’s take on A Clockwork Orange was more straightforward and plainspoken, designed as it always was to appeal to the chattering middle classes. In December 1974, she wrote of the “deliberate propagation” of the idea that there is no proof of the effects of television on “standards and behaviour“. To reject its effect, and its ability to “declaim or pervert truth, is to deny the potency of communication itself, it is crazily to question the ability of education to affect the social conscience and to train the human mind“

Which brings us nicely to the world of motion pictures and the over-reaching arm of Whitehouse, her National Viewer’s and Listener’s association (around 150,000 letter writing busybodies at the time) and the inevitable collision that occurred with the arrival on British shores of the (whisper…) home video cassette.

Ahhh, the humble video cassette. It’s tough to imagine the atmosphere into which the first home VHS players arrived. Unexpected, uninvited, unprepared, around 1977, there was suddenly talk of this magic box you could rent. Bulky, noisy and expensive, you could plug it into your telly and play tapes of films, just as you might play a cassette tape of an album through your stereo. I say rent, as research suggests purchasing a shiny new silver top-loading VHS machine in the late 70s would have set you back the equivalent of £5,000.

Well beyond the reach of all but the most filthy of lucre hoarders. UK TV rental stores, such as Rumbelows and Granada would let you have one for £50 or so for the weekend, although the choice of movies to watch was naturally sparce. Lots of Disney, certainly to start with. And even in 1984, the irreverent student TV sitcom The Young Ones was still getting plenty of laughs on its observation of the all too familiar “ohhh! Have we got a video!” novelty.

We certainly weren’t early adopters in our house. In 1980, my eldest brother was 12 and my youngest was 7. With me and my sis in-between. Perfect ages for the lure of a brand new JVC, Panasonic or Sony machine to keep the kids entertained, you might think. But we weren’t that sort of house and didn’t have that sort of money. So there was much excited envy and pawing jealousy when birthday-party school-chums announced the arrival of their machines and we were plonked down in front of pirate copies of Return Of The Jedi in warm suburban sitting rooms. (Thank you Martin Athanasiou). I eventually taped loads from the telly as a kid once my dad had given in to the bullying. Dozens and dozens of movies to watch and rewatch. Comedies mostly. But I think my first actual shop-purchase would have been something like Back To The Future, which wasn’t til about 1987. A late adopter indeed.

Anyhoo. What is little known of the era is that home-video viewing was so new and unexpected, and took off so far and so fast, it took the British Government somewhat by surprise. There was no organisation to license the import or export or distribution of these dangerous new tape-machines (VHS or Betamax) or – as we will discover, more problematically – no guidelines to police, control, censor, distribute, license or in ANYWAY control the tapes themselves.

So, in they poured by the boxful from all over the world, all sorts of titles, all sorts of subjects, all sorts of languages, all sorts of graphic visuals, all sorts of upsetting and adult imagery. And all available from a bloke in the pub or, as popularity grew, your local Video Rental store. Often just a local newsagent with a dozen or so tapes behind the counter.

Now, you would have thought this would have been an easy enough gig to get on top of. Censoring and classifying and controlling movies wasn’t a new thing. Ever since 1912, the Government had passed the task of everything from censorship of movies to the safety-regulations of flea-pit cinemas to the good ole BBFC – the British Board of Film Censors. Surely they could handle this fly-by-night “video-tape” nonsense?

Well…no they couldn’t. And they didn’t.

In 1912, The main reason for the formation of this “independent” body was the brou-ha-ha and scandal created at the release of a little movie called “From The Manger To The Cross.” As will become standard, the Daily Mail championed the public shock and rallied the nation’s outrage demanding: “Is nothing sacred to the film maker?“, and waxed indignant about the profits for its American film producers. Invited clergy had little complaint about the harmless flick, however it was a need to avoid future arguments and prosecutions and general public hub-bub that, with a flick of red tape and a patchy bit of legislation, the BBFC came into being in 1913. Not that they had much to work with, guidelines wise.

See, Government legislation regarding movies and cinemas and public showings and whatnot at the time were pretty much restricted to the only document published on the matter, the 1909 Cinematograph Act. This piece of boilerplate red tape was pretty much a safety document, much like a Corgi registered gas boiler inspection or a well-fitting seatbelt installation. The highly flammable and potentially explosive state of nitrate film placed in front of a white-hot bulb was the cause of a number of fatal fires at the turn of the century, hence in 1909 the Cinematograph Act was brought in to ensure venues were safe and stop risky back-room screenings in unventilated rooms full of dry straw and no exits.

But in 1910 the act went through a bit of a revision – some Tippex here, some highlighters there – and a Court ruling then gave the Act and its champions the right to close down a cinema for more than just safety reasons. For the first time, content of movies was now in question. And so, Censorship arrived at the box office, bought its popcorn and settled in to the front row with its copy of Empire, its scissors and its buttery fingers.

Fear, of course, spread among film makers, film distributors and everyone who’s weekly wage depended on the flickering images in the dark. Who’s going to spend thousands of pounds making a movie if some pin-striped twerp can simply ban it because it put him off his kedgeree?

So in 1913, the film industry itself hired offices at 133-135 Oxford Street in London and packed it with files, paperclips and cabinets. This, they decided, would be the office of self-regulation. Where film-directors and producers would look after their own. They’d install a board of disinterested, smart-minded fellows to watch every movie presented and give it a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down.”

To save costly expense, this could be done with early cuts of films or even with script. For a mere £2 a picture, sensible men with no investment in the movie business and no axe to grind, no profit to be made or no, in movie parlance, “dog in the fight,” would take the responsibility of making sure films shown in the UK were to a…how shall we say…standard. And the Government were happy to support this. One less thing for them to do.

Now, unlike the American Production Code Administration, which had a written list of violations in their Motion Picture Production Code, the BBFC did not have a written code and were vague in their translation to producers on what constituted a violation. Their “standards” were less prescriptive. It was more about the “feeling” of a film, than a list of do’s and don’ts. Which of course didn’t work at all, some BBFC members clearly having broader tastes and raunchier appetites than others. Clarity – or at least, an attempt at clarity – came three years later when the then president of the BBFC, T. P. O’Connor, listed forty-three infractions where a cut, trim or edit in a film may be required. And so it all begins…

You don’t need me to tell you what some of these infractions were. It was 1916 for heaven’s sake. But if you guessed scenes that included: Men and women in bed together; Illicit relationships; Nude figures; Offensive vulgarity, and impropriety in conduct and dress; Indecorous dancing, and my personal favourite “Subjects dealing with India, in which British Officers are seen in an odious light”, then you’d be on the money.

Much has been written on the changing role of the BBFC since its creation in 1913 and its handling of “From The Manger…” to more recent controversies. I can recommend the excellent “Behind The Scenes At The BBFC” edited by Edward Lamberti.

Here’s a link if you fancy downloading a sample.

Plus more details on all of this stuff on the BFI website:

https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/history-british-video-nasties

Bannings and cuttings, arguments on the right or wrong age to see certain images, how many “fucks” can you say in a PG13? How many tits can you see in a 15? How much blood and violence is too much blood and violence? All this via tabloid bothering scuffles over “Crash,” “Irreversible,” “9 Songs,” “Antichrist,” “The Exorcist,” and of course, “Life Of Brian.” Hell, even the family big-dog romp “Marmaduke” needed a trim of the word “spaz” before it could be released with a U certificate. The fact that its initials now stand for “British Board Of Film Classification” rather than “Censorship,” will tell you a great deal.

But what of Mary Whitehouse? We left her at her kitchen table, dunking a biscuit in her tea and sharpening her Parker Duofold. Meanwhile, as the seventies ended, the Government stood about watching crate after crate after crate of dodgy, knock-off, pirate, low-quality, shocking, perverted, horrific and scandalous VHS tapes pile onto British docks and making their way, both honestly and sneakily, into cosy sitting rooms without the BBFC doing a thing to stop it.

Why didn’t the BBFC step in to start certifying these tapes? This one is for families, this one is for adults? This is a PG, this is an 18? Get a bit of classification going, stop the wrong tapes landing in the wrong hands, just as it had kept audiences in check for the last sixty years? Well fact is, the BBFC had nothing to do with this new VHS trend. Nothing. No power, no authority, no control. As the BBFC had been set up to help manage and monitor the public showing of films at cinemas, it had no rights or responsibilities when it came to “home entertainment.” Any more than a traffic warden can tell you to tidy up your garage.

And the BBFC were in no hurry to add “home VHS tapes” to their to-do list. I mean, can you imagine? Already over-stretched with having to watch every movie presented for distribution in the UK, suggest cuts and trims and recommend adjustments and argue split second shots with producers and studios? How on earth could it cope with the thousands upon thousands of home-made, foreign, dubbed, knocked-together, cheapie tapes that absolutely flooded the market as the 70s became the 80s and EVERYONE had a video player in their lounge? Well they couldn’t. So they didn’t.

For a while, it was a lawless wasteland. Nothing stopped anyone becoming a video-importer. Nothing stopped suburban camcorder-wielding swingers filming their own lusty shag pics and handing them out around the Rotary Club for 2 quid a time. Nothing stopped once harmless and safe corner tobacconists becoming one-stop shops for hard-core porn and gruesome snuff pictures. There were no certificates, no age-recommendations, no restrictions, no censorship. Anyone with 50p and a home-made plastic card could happily rent Confessions Of A Window Cleaner, I Spit On Your Grave, Cannibal Holocaust and All Holes Filled With Hard Cock, along with their Slush Puppy and Beano.

A great time to be a teenager, as you would imagine.

But, as far as righteous indignation, flag waving, stamping and letter writing, an even BETTER time to be Mary fucking Whitehouse. The words “red rag” and “bull” seem appropriate.

So what happened?

Well it didn’t take long. With a glut of hard-core porn, violence, abuse, animal cruelty and general degrading videos full of naked nuns and horny Nazis, never mind brain-eating zombies and rapey serial killers flooding Britain’s high-street, Mary Whitehouse was soon being pushed forward as the spokesperson for “well-meaning Britain.” Famous as she was for her campaign to clean up TV, toddlers being exposed to horror and sex and violence through their TV screens got her campaigning all anew. What good was trying to get “bloodies” and “bastards” removed from evening TV comedy scripts if, at 4.30 in the afternoon, Schoolchildren could slap a copy of “Elsa: She Wolf Of The SS” into the family Panasonic?

So Mary Whitehouse and her crack squad of letter-writing complainers set about the stationery shops of Britain and bought all the fancy pink writing paper and flourish fountain-pens they could and got to work. This was going to take a concerted effort if they were to “Ban This Sick Filth.”

The British, of course, love their freedom of speech. Their human rights. Their God-given permission to do as they please. But hoo-boy, they much prefer a scandal. Something to be shocked about. Something to complain about. Something to gasp and faint and be outraged by. So in the first part of the 1980s, tabloid headlines began to fill with stories of lurid movies, shocking films, revolting scenes and degrading acts that were entering innocent homes via these…video…these video…NASTIES!

Oh and we love a dumb catch-phrase too.

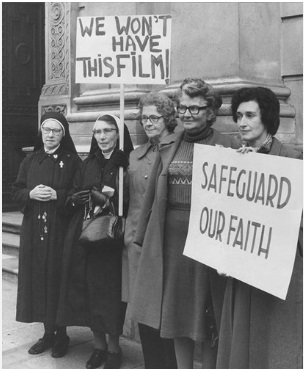

Letter and complaints were penned, rallies and marches were held. Local townswomen brandished banners and bunting, reverends and vicars waved Bibles and gnashed teeth. Often their own, often any teeth that were hanging about the vestry. Journalists smelt both blood and sales receipts and for a few months, no-one in Britain could watch a TV news show or pick up a newspaper without reading of hearing Mary Whitehouse rant and rave, eyes wide, shocked and stunned, aghast and agape at this “shocking filth” that must, must MUST be stamped out.

Headlines screamed: “Seize The Video Nasties!” “Ban Video Sadism NOW!” “Burn Your Video Nasty” “Four Children In Ten Watch Video Nasties” “Judge Blames Video Nasties For Murder” “I Heard Voice Of Video Michael [Myers]” and “Keep Nasties From Our Kids.” And the Government, bullied and harangued by the triple threat of the NVALA, some vote-thirsty populist politicians and the very public face of Whitehouse herself were pushed into action.

How can they “Keep Nasties From The Kids?” Well..? Ban them? What all of them? No, some of them. That’ll do it.

What followed with the infamous 1984 Video Recordings Act was a hasty attempt to get the worst of the worst off the streets and out of the hands of children. Or indeed, out of the hands of anyone.

It helps if we look at the fine print of what this Act Of Parliament actually required. Pretty much it states that ALL commercial video recordings offered for sale or for hire within the UK must carry a classification that has been agreed upon by The BBFC. Simple as that. The BBFC are allowed to use their standard U, PG, 12, PG13, 15 and 18 certifications. And it is a criminal offence to supply films to the wrong age-group or those who appear to be too young. Hence all that “show your ID” stuff in shops. And the “click you are over 18” buttons on streaming services. Any movie that is refused classification by the BBFC or is missing classification cannot, under the Act, be legally sold or supplied to anyone of any age.

Naturally some tapes don’t need a certificate as they are deemed spectacularly harmless to anyone any age. Eg. Non violent sport, religion or music. Although bung some boobs or blood in a pop video (I’m looking at you Duran “Girls On Film” Duran and Michael “Thriller” Jackson) and your pop video “greatest hits” gets an irritating 18 Certificate.

Oh, and that “educational” loophole? Yeah, you ain’t getting round that easily. Exemption may be forfeited if the work depicts “excessive human sexual activity or acts of force or restraint associated with such activity, mutilation or torture of humans or animals, human genital organs or urinary or excretory functions, or techniques likely to be useful in the perpetration of criminal acts or illicit activity.” So disguising your violent porn as a “How-To-Guide” may not get you out of court.

So that was the act. 1984’s (ironically) sweeping move to get the nice folk at the BBFC to step in and do for video-tape what they’d been doing for cinemas for nearly a century. And the world relaxed.

For about an hour and a half.

Because Mary Whitehouse and her group weren’t satisfied with just that. Yes, making some movies 18 certificates and plastering “Adults Only” might reduce the chance of youngsters being depraved and corrupted. But what if dad left the tape lying about? What if a group of scallywags climbed on each other’s shoulders and draped a long raincoat over themselves and passed themselves off as a 7 foot grown up, false beard and pipe to match? Wasn’t there STILL a danger?

Well yes, everyone who went to school for more than 5 minutes said. Of course. A risk. Just as there is for driving a car under age. Or drinking under age. Or smoking under age. Or voting under age. But you do your best to get families and schools and responsible adults to monitor what’s going on and hope for the best. I mean, what’s the alternative? Ban the movies for EVERYONE?

Somewhere Mary Whitehouse smiled. Yep, that’d do it.

There are films sooooo filthy, so disgusting, so horrendous and so corrupting to ANY mind, child or adult, that they simply shouldn’t be allowed to be seen. Or shared. Or owned. Or distributed. Or talked about. Or even admitted to exist.

What? Everyone said. What are you talking about? Which films? And more importantly…where can I get them?

And so the “Video Nasty” was born. A tabloid-feeding phrase to catch the eye and to be applied to the worst of the worst. Films sooo dangerous and disgusting, they should be illegal. Famously Mary Whitehouse claimed never to have seen any of them. But she didn’t need to. She could sense the filth.

Campaigning strongly from the front, with well-meaning family groups and church representatives bringing up the flanks, prosecutions commenced against individuals engaged in trades exploiting these allegedly “obscene videos.” But how to tell the obscene from the merely misjudged? The gory from the gratuitous? The sexy from the silly? Did they expect local policeman and councillors to pull up a chair and watch EVERY movie for rent at Jessy’s Video Emporium, Tobacconist & Newsagent? No, of course not. To assist local authorities in identifying obscene films, the Director of Public Prosecutions released a list. THE LIST.

Seventy Two films made it onto the list. 72. Who chose them, how they were chosen and what criteria was used to decide – for example – that The Exorcist was no problem, but The Evil Dead was unwatchable. That A Clockwork Orange’s violence was palatable whereas Straw Dogs would ruin the lives of anyone who touched the video box? It’s not clear. From the list of tapes it became illegal to rent or distribute and which could be taken and destroyed and prison sentences issued, the list seems somewhat…knee-jerk. Clearly there are themes. If your movie has “Cannibal” in the title, chances are it’s getting seized. If it has “Don’t…” in the title, again it’s going in the bag. “Blood” “House” and “Death” aren’t going to do you any favours either.

Full list here, if you fancy it.

https://www.imdb.com/list/ls051364249/

So well-meaning coppers went door-to-door to video shops and newsagents and pubs and clubs and seized tapes and made arrests.

This insight from the BFI article, reproduced with no permission:

“That filmography, which underwent several revisions, was something of a mess. Policemen charged with seizures of tapes just had a mimeographed, typewritten list to go by, so classing Tobe Hooper’s Death Trap (1976) as a nasty when Sidney Lumet’s Deathtrap (1982) was on the same shelves was bound to cause mix-ups. The list was also arbitrary. Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) was a nasty while his equally explicit and – to 2021 eyes – more problematic Blood for Dracula (1974) escaped the net.”

Oh yes.

In addition, a second list was released that contained an additional 82 titles which were not believed to lead to obscenity convictions but could nonetheless be confiscated under the Act’s “forfeiture laws”. In a sense, not technically illegal to own…but not something you want to be caught with. Not, as they say, a “good look.” And then a third list of pretty much “everything else” you wouldn’t necessarily put in the front window display.

So there we are.

Wikipedia helpfully – although one can never be sure accurately – provides some insights into movies that made it onto these lists. Here it is:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Video_nasty

But they break down like this:

THE ORIGINAL BANNED 72: (DPP List 1 + DPP List 2)

DPP Section 1 List. Of the original scaremongering list of 72 “OMG!!” horror movies, this first list of 39 are the movies that were successfully prosecuted and banned. Those found in possession of any of these 39 were liable to face personal prosecution, resulting in fines and potential jail sentences. These tapes include such notorious family favourites as SS Experiment Camp, Faces Of Death, Cannibal Holocaust and Last House On The Left. However it’s important to note that 33 of these have since been reclassified and recut and released in some format or another.

DPP Section 2 List. The remaining 33 of the Banned 72. The films in this list, including The Evil Dead, Cannibal Terror, The Toolbox Murders and The Witch Who Came From The Sea could be seized under Section 2 would make the dealer or distributor liable to prosecution for disseminating obscene materials. However these weren’t personal prosecutions and destruction of the material was usually enough.

DPP Section 3 List. Yeahhhh, the rest of them essentially. These tapes were liable to seizure and confiscation under a “less obscene” charge. Tapes seized under Section 3 could be destroyed after distributors or merchants forfeited them. We’re talking “Dawn Of The Dead”, “New Adventures Of Snow White” and of course “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.”

So that’s it. A lot of storm in quite a controversial teacup. For a few months, the hottest topic in the UK. Both successful in getting certain movies off the shelves and out of the “easy” reach of the young. But of course, as Kim Newman puts it beautifully, “…Inevitably, the DPP list was used by horror fans like the I-SPY Book of Garden Birds – there was competition to see who could see and tick off all the films…”

Which is where we came in. I hope this little tour has made more sense of the project, the list, what’s on it, why and how the whole thing came to be.

I a sure I have made Mrs Whitehouse a bigger part of this story than she should be. There was ALWAYS going to be a backlash against obscenity one way or another the the British public was merely waiting for SOMEONE to speak up so they could tut and agree and be “thoroughly disappointed” by the state of the world. Sigh. But she put her name and face to it.

Greater insight into her and her work can be found in this hugely entertaining read, “Ban This Filth!” so enjoy that.

I am hoping this site will get through ALL the movies on ALL the lists. Most of them, 40 years later, being available on Netflix, Amazon Prime, Shudder and, would you believe, free for all on YouTube.

Times have changed. Both here and across the pond in the United States. Who of course, have always had their own White-House to worry about. What was once too shocking for human consumption is now free to view on your phone. But there’s huge fun to be had in trawling through the grue and the gore and the ghastly and the ghostly. I hope you’ll join me.

Richard Asplin | Dec 30th 2022 | Surrey